In 2009 I collaborated with my good friend, scenographer Antonella Diana, on an interactive installation called “Let ME Go“. It was based on the Sumerian myth of the goddess Inana’s descent into the underworld to visit her sister. Her journey involved passing through seven gates and at each one she was required to give up a symbol of her power (in Sumerian language these symbols of power were called Me). In our individualistic and materialistic times, this story offers a powerful lesson in letting go, relinquishing, stripping down to what is essential.

I’m not very good at letting go. My natural instinct is to hoard, to hold on to objects that hold memories and to keep odd or broken things in case one day they might be useful. But this last year has been all about letting go, and slowly I am getting better at it – or at least, thinking about it.

In May, I had to let go of my mother. She had a good life, and lived to a good age, and for my entire life had always been there – at the end of the phone, in her little house and lovely garden, cooking dinners and cakes, knitting and mending, beating me at Scrabble or enjoying quietly doing a jigsaw together. Now she is not there any more. It’s a huge hole.

In May, I had to let go of my mother. She had a good life, and lived to a good age, and for my entire life had always been there – at the end of the phone, in her little house and lovely garden, cooking dinners and cakes, knitting and mending, beating me at Scrabble or enjoying quietly doing a jigsaw together. Now she is not there any more. It’s a huge hole.

I let go of most of my work over this last year. The months of caring for mum, organising her funeral and emptying her house didn’t leave time for much else. I unsubscribed from many lists (that felt so good!) and stepped back as much as possible from my ongoing projects. It was easier than I anticipated, and I feel so much lighter, with much less emails flooding in and less commitments weighing over me. I’ve learned to ignore “opportunities” and have almost stopped making funding applications – unfortuntely I can’t stop completely (yet), but it’s allowed me to reflect on what a huge drain it is on my time and creativity. I’ve done so many large, unsuccessful, applications during the last three years that it is soul destroying, crushing, and not at all what I want to be doing. Letting go of work has meant rejecting the intense pressure that most (all?) artists put on ourselves to maintain visibility in one’s particular corner of the art world, and this has given me a great sense of freedom. Letting go is good!

I am proud to say that I’ve managed to let go of some of my STUFF. Not a lot, but some. I carefully went through my stored clothes, including my vintage frock collection (really!!), and released anything that doesn’t fit me or needs mending that I will never do, and some things that I didn’t really like any more (check out Prue’s fabulous shop Box of Birds in Port Chalmers, where many of my – and mum’s! – things are awaiting the next phase of their lives). I discovered a box of financial documents dating back 20 years, which was a surprise as I thought I’d been ruthless with paperwork, but there you go – hoarding! I spent an evening feeding the paper into Georgie’s potbelly stove. And I passed on kitchen things, towels, bedding and furniture to a friend’s daughter who will go flatting next year.

I am proud to say that I’ve managed to let go of some of my STUFF. Not a lot, but some. I carefully went through my stored clothes, including my vintage frock collection (really!!), and released anything that doesn’t fit me or needs mending that I will never do, and some things that I didn’t really like any more (check out Prue’s fabulous shop Box of Birds in Port Chalmers, where many of my – and mum’s! – things are awaiting the next phase of their lives). I discovered a box of financial documents dating back 20 years, which was a surprise as I thought I’d been ruthless with paperwork, but there you go – hoarding! I spent an evening feeding the paper into Georgie’s potbelly stove. And I passed on kitchen things, towels, bedding and furniture to a friend’s daughter who will go flatting next year.

Emptying a home after someone dies is a sobering exercise and good encouragement for curbing hoarding instincts and letting go. Mum’s house is the third deceased estate I’ve been involved in, and by no means the worst. She was always quite minimalist, and had endeavoured to reduce things down in her later years, but this meant that most of what was there was special. Most. There was of course the old toothbrush collection (useful for cleaning but how many do you really need?), the tiny medicine bottle collection, the cork collection, the twisties and rubber bands, the paper and plastic bags, the threadbare sheets that had been cut down the middle and sewn together again at the outside edges, the miscellaneous seeds, buttons, wool (waiting to be spun, waiting to be knitted), fabrics (waiting to be mended, waiting to be repurposed), jars of useful nails and screws, strange old tools, years of New Internationalist, Forest&Bird, and Organic NZ magazines, years of appointment diaries and calendars … gifts and ornaments that meant a lot to mum but little or nothing to us.

Naturally it makes one think of one’s own detritus, that someone else will have to deal with after I finally and fully let go. I look at everything around me – my books on the shelf, the magnets on my whiteboard, my clothes, ornaments, jewellery, cards, letters … the documentation of my work, festival programmes, appointment diaries and journals, notebooks, scribbles … drawers full of old technology … and this isn’t even the boxes in storage in NZ. I have too much stuff.

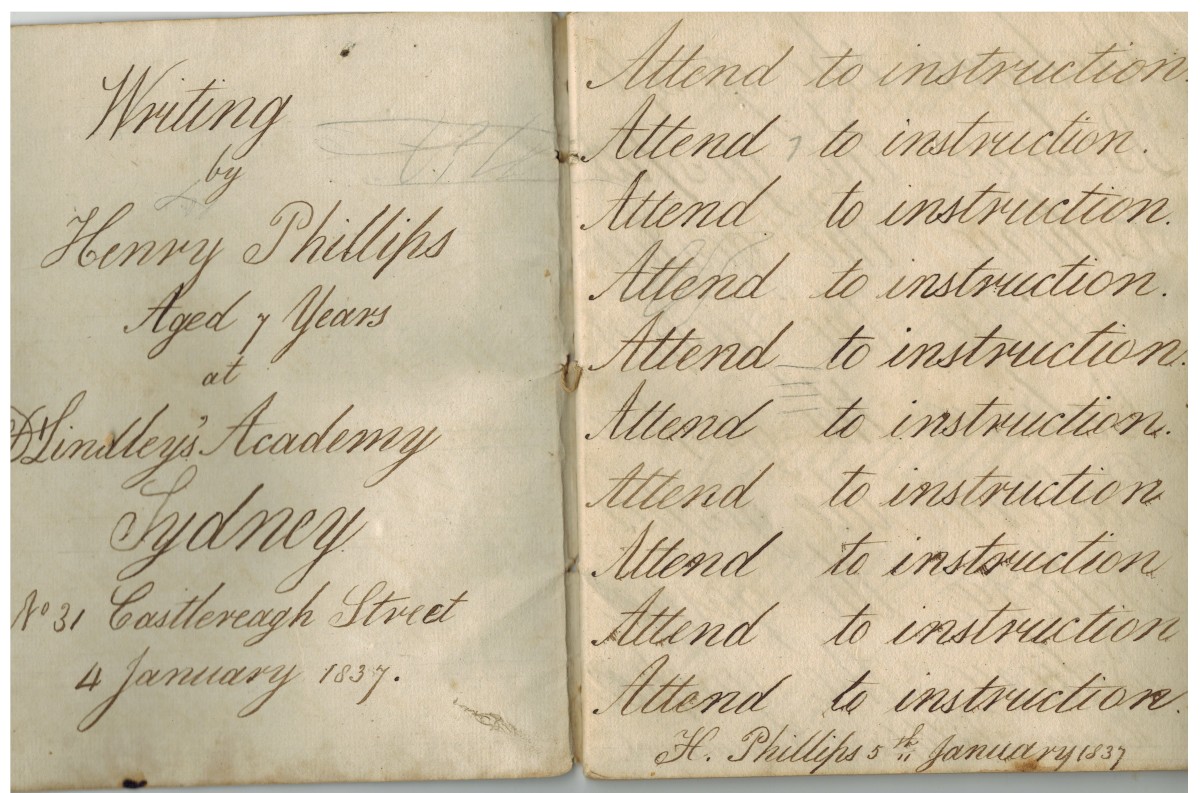

But hoarding and archiving are two different things; and archiving is something my family are pretty good at (librarians and archivists are very closely related). On my mother’s side the family archives go back more than 200 years. There are bundles of letters exchanged by my great-grandparents during the first world war, ancient books, and very early photographs. One of my favourite treasures is a school exercise book from 1837, in which my ancestor Henry Phillips, aged seven at the time, is practising his handwriting, copying out moralistic Victorian statements. It’s difficult to imagine a seven-year-old today doing this kind of work. I’m glad this book has somehow survived, and realise it’s special because it’s the only one. We don’t need to keep everything.

But there’s still one more thing I must let go of before the year is over – my left femoral head (hip joint). I had my first hip replacement, in New Zealand, where it’s quite normal to request a removed bit of bone. It was given to me in a plastic specimen container after the operation and went into the freezer at home for a while. Later I boiled it, then buried it in the garden for a while, to clean it. Now it’s in my storage, waiting to join the rest of my bones when I let go of life. In Germany it’s a different story: my surgeon actually laughed when I asked if I could have the bone. Germans are funny about dead bodies, bones, and even ashes – none of these things are allowed to be taken home. I come from a culture where it’s normal to have someone’s ashes on the mantlepiece and for whanau to sit at the marae with someone in an open coffin for days. But I’m in Germany and I must allow my left femoral head to be consigned to the hospital garbage. That really takes some letting go!

There are of course many things that are worth holding on to, such as the Magdalena network; and UpStage, my long-term online performance project, which in 2024 celebrates 20 years! Letting go of some things that I’ve cared about makes the thing I choose to hold onto more valuable and, importantly, more fun.